Ryszard Kapuscinski’s works addressed leading development issues of the 1970s, 1980s, and (arguably to a lesser extent) the 1990s. Have the world’s development challenges changed since then? What was the biggest challenge then and what is it now?

In the period of the 1970s and 80s, development was largely seen in terms of modernisation and economic growth. Key challenges turned on enabling countries to establish stable, growing economies through an appropriate balance between industrialisation and agriculture and rural development. Concerns with poverty reduction and social development challenges such as health, education and gender were growing in significance, but often marginalised. And as the neo-liberal era of the 1980s set in, the state-led development agendas of the 1970s gave way to the promotion of free markets. Through the 1980s and into the 1990s, dealing with the fallout of structural adjustment and related programs through a renewed emphasis on human development came to be seen as a critical challenge, with states and civil society organisations frequently assuming responsibility.

The last few decades have witnessed major progress in these aspects of economic and social development in many parts of the world. Yet they also reveal a series of paradoxes and contradictions. First, growth has accelerated in many countries but has been accompanied by growing inequalities of many kinds. Global income growth has been very unevenly shared, concentrated in rising middle classes in India and China and in a booming global elite, but with the poorest percentiles locked out, and a declining shared of growth amongst the middle classes in the developed world. Old industrialised countries, emerging middle income ones, and poorer countries are almost all experiencing rising economic inequalities. These intersect – nationally, and in terms of people’s lived experiences – with other kinds of inequaity – social and gender, cultural, political, and in terms of place and knowledge. Inequalities matter fundamentally because they are unfair and unjust, but they also affect other development proprities. Inequality can hamper economic growth, and certainly reduces the impact of that growth on poverty reduction. Health and nutrition are worse in countries with higher income inequality. Inequalities are threatening our democracies, and contributing to rises in conflict – and more.

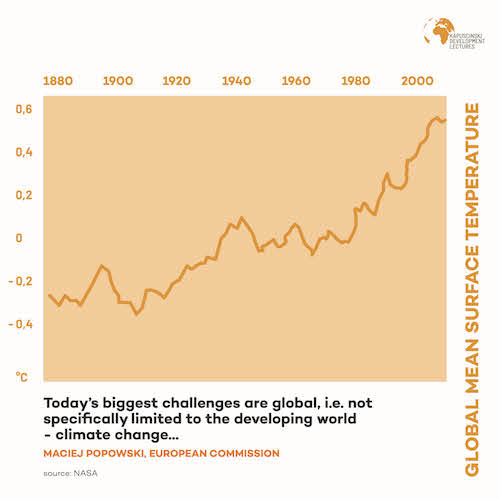

Second, dominant development paths are proving deeply unsustainable in environmental terms, with climate change, biodiversity loss, land and water degradation and pollution threatening our ability to thrive on a pressurised planet. What were relatively marginal development issues in the 1970s and 80s have moved centre-stage, with growing attention going hand in hand with growing evidence of trends in human-induced climate and environmental change, and its devastating impacts on lives, livelihoods and societies across the world. Development has, by necessity, become sustainable development, and a central challenge is to find and unlock pathways which can ensure human thriving while avoiding further threats to our biophysical life support systems.

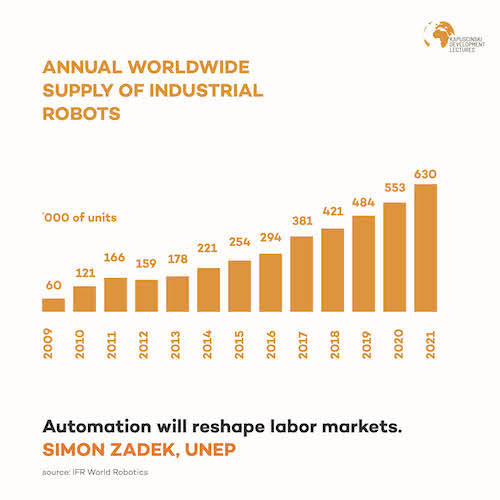

Third, the burden of insecurity, and its counterpart, lack of inclusion, affects historic numbers of people across the world on a daily basis. Both nation states and the international community have invested intensively in military security, yet conflict and violence affect many people’s lives. Many face complex, protracted emergencies in which political insecurity intersects with disease epidemics and natural disasters. We have a growing migrant crisis as unprecedented numbers of people leave their countries to escape war, repressive regimes, political alienation or economic hardship. While political participation is given more attention, there is growing distrust in political institutions. Technological innovations offer once unimagined opportunities, yet are also exposing people to new threats, exclusions and invasions of privacy.

In this context, development needs to move from a narrow focus on economic growth and poverty, to navigating complex challenges in ways that reduce inequalities and build more sustainable, inclusive and secure futures for people and societies. (i) Reducing inequalities, (ii) Accelerating sustainability and (iii) Building inclusive and secure societies can be seen as the major defining challenges of our time. Yet there are no single motorways or roadmaps to progress in this new era of development. Multiple and flexible pathways of change and transformation that adapt and respond to diverse contexts, needs and priorities will be required, supported by new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating.

Some people dismiss sustainable development as an aspirational vision, others an unattainable fantasy, and still others absolutely necessary to our future. In this age where few seem interested in working for the collective good of all, what’s your argument to convince others that it is necessary to change the way we develop?

Climate change, biodiversity loss, the degradation of land, vegetation and water resources, pollution whether of the air we breathe or of rivers and oceans increasingly choked with chemicals and plastic – these problems are inextricably linked and affect people across the world. They are the consequences of dominant development pathways which have brought prosperity to some, but at deep cost to non-human nature and people’s safety, health and livelihoods locally and globally. Indeed, there is growing evidence that current development paths risk irreversible damage to the earth’s biophysical life support systems, with further shocks and stresses in store that will affect us all, undo development progress and block it for future generations. There is therefore an urgent need to seek new development pathways that are both sustainable, and equitable. These will require transformative, not just incremental change, recognising that business as usual is not an option, and fundamental shifts are needed in some of the key structures, institutions, systems and norms that shape our societies and economies, along with the transformational politics to deliver these. While this is a major challenge, it is not unattainable. Transformations to sustainability are already happening in some places and around some issues, led both by top-down international and government action and policies, and crucially by grassroots action by citizens in rural and urban settings. Building the political momentum to intensify and grow these initiatives, and to challenge the ‘lock-ins’ that block pathways to sustainability, are key tasks ahead.

What is the biggest challenge/hindrance to successful development?

What area of development or Global Goal do you think sustainable development hinges on? Which one is at the core of all the others?

The Global Goals lay out an ambitious and important agenda for both people and planet, to which all countries have committed. This is a vital and positive step in meeting the challenges of sustainable development. All 17 goals are important, and it is in their combination that progress by 2030 and beyond can be expected. There are also important synergies and tensions between the goals which need to be acknowledged and addressed. For instance meeting the goal for food production could compromise the water goal if agricultural strategies do not take into account surface and groundwater needs; on the other hand opportunitie exist for multiple wins in addressing food, energy and water together. Addressing climate change goals and targets could compromise goals around poverty, tackling inequality and gneder equality if technological and market schemes dispossess local people of rights and livelihoods; on the other hand appropriate policies and strategies could address all these goals together, for instance by building on grassroots initiatives with women’s leadership, or building in appropriate safeguards. Because of these interactions, it is not appropriate to define any particular goal as the most important for sustainable development. People do not live their lives in separate silo-like goals, and nor should responsive, transformative development.

Alongside the significance of the SDGs themselves are their cross-cutting principles and approaches. The imperative to ‘leave no one behind’ is a vital step in forging a development agenda that is genuinely inclusive, and which tackles extreme forms of marginalisation – whether related to poverty, ethnicity, disability, peace, gender or intersections of these. The SDGs are also universal, applying to all countries and people. This is a is a major step in dismantling the problematic divides between so-called North and South, developed and developing country, which have pervaded so much aid and development discourse and practice. Instead, we can now look properly to development as positive change for everyone, everywhere. We can fully acknowledge and address the global-local interconnections between people and places around challenges such as climate, finance, food, and pandemics. And we can forge a development agenda that is about mutual and multi-way learning and co-operation in all directions.

What’s the most striking thing you have personally witnessed in relation to development? i.e. a challenge, opportunity or just personal observation about a human story.

I’ve witnessed and experienced many striking things in relation to development, but a story from recent times illustrates some of the themes I have addressed above: the importance of interconnected challenges in a complex world, and the importance of combining different forms of knowledge and practice – grassroots as well a sglobal, social as well as technical – to address them.

The spectre of a deadly disease emerging in a remote place, spreading rapidly to become a global pandemic is the stuff of nightmares. This ‘global outbreak narrative’ fuels popular media, and now a new wave of global ‘pandemic preparedness policy’. Ebola has become paradigmatic, topping the World Health Organisation’s latest priority disease list. This isn’t just because Ebola is a particularly dramatic haemorraghic fever transmitted through body fluids and killing more than half those infected, but also because in 2014-2015 the global outbreak narrative came true. The Ebola epidemic that began in the village of Meliandou in the Guinea-Sierra Leone-Liberia border region in December 2013 spread fast through the towns and trade routes of this highly-peopled, mobile region, and cases – and fear of them – reached neighbouring countries, Europe, the US and the world. By January 2016 when all countries were finally declared Ebola-free, the death toll was just over 11,000, with 17,000 survivors struggling with the medical and social fallout. It was a devastating crisis – but it could have been much worse. The story of grassroots and social knowledge is critical to this.

Why was this? The problem was that by August 2014, when the World Health Organization belatedly declared the epidemic to be a so-called „public health emergency of international concern”, it was already out of control, with scientists predicting not thousands but millions of deaths. The early international response by humanitarian agencies had foundered, largely for socio-cultural reasons. Many villagers suspected that both the virus, and alleged attempts to control it, were plots to repress their livelihoods and practices, or even kill them. Villagers stoned response agencies’ vehicles and dug trenches across their bush roads to keep them out. People hid and cared for their patients in their remote farm camps rather than bring them to Ebola Treatment Units, and sometimes ‘stole back’ patients treated there. Funerals were quickly identified as a key moment for transmission, when bodies are at their most infectious, and local practices involve touching and visits by kin – yet people resented and resisted the external teams sent in to conduct so-called safe burials. And as the response scaled up, so did local anxieties about it.

Really worried about what was unfolding, a group of anthropologists in Sierra Leone and the UK who had worked for decades in the region on various development-related issues wondered what we could do. We set up an Ebola Response Anthropology Platform, and established links with networks of concerned anthropologists that also emerged in West Africa, Europe and the US. Together. We mobilised social science knowledge in real-time to re-shape the public health and humanitarian response, away from the top-down approach that was clashing so badly with local values and fuelling resistance that magnified the crisis, and towards a more respectful, community-engaged approach that appreciated and built on people’s own social and cultural logics, practices and innovations.

Take funerals: our work showed the need to see them as part of a longer period of caring for the extremely sick by kin; and their social and cultural significance, ensuring people become ancestors, social faults are addressed, and matters of inheritance settled. At one point there was a stand-off in a Kissi village where a pregnant woman had died of Ebola; villagers insisted that the fetus be removed before burial, to avoid the social fault of ‘maa’, in which regenerative cycles of generations are mixed, with devastating consequences for land, crops and people. The burial team refused because of the infection risk. Mediation by an anthropologist and a local healer helped broker a creative alternative; a sacrifice that would appease the relevant spirits without the fetus being removed. As in examples like this, communities were willing to adapt their practices to balance social and infection risk; but agencies needed to appreciate their social significance to support this balancing. Such understanding fed directly into new guidelines for ‘safe and dignified burials’ with community involvement.

Or take local anxieties about the response: far from being the ignorance based ‘rumours’ that agencies initially assumed, our work showed their logics embedded in the region’s experience of development and inequalities. The idea that foreign agencies might be trying to depopulate an area to take land – or that Ebola is being spread by white miners – are all too feasible given people’s lived experiences of land and resource grabs and disposession. One of the most devastating incidents in the epidemic, when villagers in the Guinea forest village of Womeh out of fear attacked and killed a 6 person Ebola sensitisation team, happened less than 10 km from Mt. Simandou, the planned site of the largest integrated iron-ore mine and infrastructure project ever developed in Africa by Rio Tinto Group, BSG Resources and the Aluminium Corporation of China (Chinalco). Ebola also became embroiled in longstanding ethnic and political tensions. For instance in Guinea, the epidemic’s epicentres in the forest and coastal regions are also heartlands of ethnic groups opposed to the Malinke-led party in power. A politicised response by government was easily interpreted as genocide. By explaining these tensions, we were able to support agencies to tailor their messages and teams – for instance by working through ethnically trusted or neutral officials.

Our Platform directly shaped humanitarian and development strategies. It supported the UK government’s strategy in Sierra Leone, becoming a first-time social science sub-committee of the UK Government Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), directly advising the Chief Medical Officer and Chief Scientist. Impacts included the decision to develop Community Care Centres for initial triage and isolation of cases, as a more acceptable and accessible alternative to the large Ebola Treatment Units which people so feared. We also directly informed the social mobilisation efforts of the Sierra Leone government and NGO-led Social Mobilisation Action Consortium, highlighting how community learning and behaviour change was turning the epidemic round, and how to build on this in ‘Community Lead Action on Ebola’ efforts which eventually reached 67% of communities in Sierra Leone.

International agencies have recognised this. Margaret Chan of WHO said in 2015 ‘we have learned the lessons of community and culture’, and WHO’s re-vamped Health Emergencies Programme has a major emphasis on community engagement, as does UNICEF’s new Health Emergency Preparedness Initiative (HEPI). The importance of social science knowledge has been recognised – at the invitation of UNICEF and USAID we’re now running a broader social science in humanitarian action platform, and agencies are calling for the development of social science protocols to be ready for quick use in further outbreaks, of all priority diseases.

Outbreaks and potential pandemics will recur in our current and future development era – although when and where we cannot be certain. These are part of the protracted crises that affect so many. What I think we can be sure of is that alongside medical technologies and epidemiology, social knowledge – and the ability to mobilise it in real time – will be critical parts of the world’s ability to be ready and respond, and crucial to addressing humanitarian and development issues.