Kapuscinski challenged us in his writings to see the world as it is, and at the same time to see it in fundamentally different ways to convention. Sustainable development likewise challenges us to understand not only where we want to get to, the first sixteen ‘goals’, but through the seventeenth and the broader 2030 Agenda to shape pathways to success based on a fundamental reappraisal of both where we are and how ambitious action can be effective in today’s world.

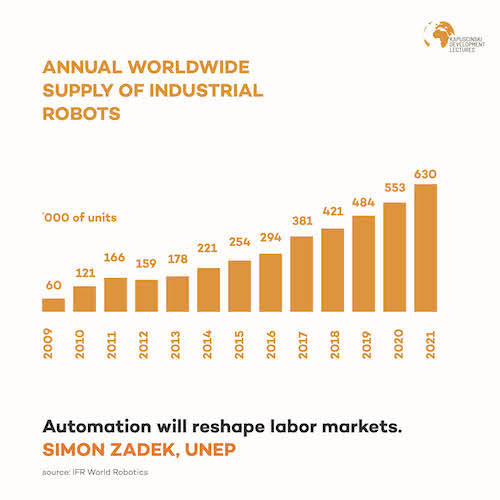

More of the same, in a nutshell, will not get the job done. This is not just because we made bad decisions in the past, but because the world around us is changing, demanding new approaches to old as well as new problems and opportunities. The fall in global poverty and inter-country inequality over recent decades, for example, largely resulted from China’s rise, a driver that will not repeat itself any time soon. Automation will reshape labor markets and the basis of international competitive advantage in years to come in ways that require different development models as export-led growth becomes less likely for many developing countries. Climate change is now upon us, and means a world of growing numbers and impact of shocks, with livelihood, security and political implications.

Actually, we are overwhelmed by solutions as much as by oft-repeated problems. Perhaps for the first time in human history, we have the science, the technology, the finance, and the know-how to deliver on sustainable development. Our greatest challenge is in how best to organise the delivery of well understood and quite affordable solutions. Our failure to organise is widespread, from weakened multilateralism, to corporate disfunction, to inadequate civil society organisations, and to short-term financial markets. The state formations, civil forms of action and the market institutions we have inherited are proving inadequate to harness the potential of our inventiveness and make it widely available. Digitalisation provides the prospects of a frictionless world of networked opportunities, certainly, But without institutions that can form and oversee equitable rules, this technological surge is more likely to drive further instability and injustice. Our vision of society’s underpinned by human rights and individual choice is threatened by the deterioration of our belief in election-based democracies, the equalising effects of information, and our capacity to sustain empathy at scale in the face of disruption and uncertainty.

Our capacity to organise is inter-twinned into our evolutionary process. It is more than anything what makes us able to actualise our imagination in becoming what we are, a technological species. As a civilisational building block, we exist as long as we can organise in ways that are commensurate with new challenges and opportunities. Reforming the UN is but one tip of this imperative. We need likewise to reinvent the purpose and logic of business and the state, and their respective interfaces with each other and the underlying, organic dynamics of self-organisation.