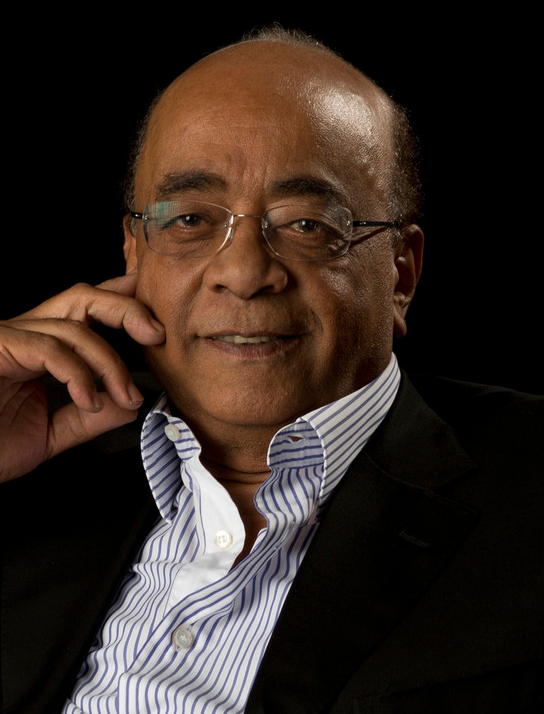

Professor Bach addressed the relationship between the European Union (EU) and Africa. While emerging market countries have recognized the opportunities Africa holds, Bach queried the EU’s appreciation of the strategic importance of Africa. Africa is still too often viewed as a ‘dark continent’, made up of neo-patrimonial, quasi-states which offer few prospects for development. A victim narrative has been constructed whereby Africa is believed to epitomise the pitfalls of globalisation. This has given rise to a moralistic and humanitarian approach to Africa by the EU, which while well-intentioned, has not, arguably, been in the best interests of Africa. Failing to define Europe’s geo-strategic interests in Africa has fostered the impression in EU circles that Africa is a ‘dispensable continent’ when it comes to setting the agenda of world affairs. Bach argued that the EU’s vision of Africa needs to change if Europe does not wish to be sidelined in the future development of Africa.

It is true that in recent years there has been a move by the EU to chart a new course in EU-African relations. The Joint Africa-EU Strategic Partnership (JAES) which was adopted in 2007 following the second Africa-EU Summit in Lisbon, has significantly altered the tone of the dialogue. Bach argued however that the JAES has, up till now, not been very successful. It has suffered from both a lack of funding and weak enforcement capacity. Furthermore, the African Union (AU) – the key organisation for EU-African engagement- suffers from a ‘fallacy of composition’. Its members are often also party to other organisations, treaties and frameworks which at times compete with the stated aims of the AU. Bach therefore called on the countries of the AU to rationalise their membership in order to strengthen the negotiating power of the AU.

When it comes to institutionalising a model for regional integration and cooperation, the EU model has been highly successful. The lure of the benefits of EU membership has spurred on liberalising and democratising reforms and conferred upon the EU project a sense of ownership and legitimacy. It remains to be seen however whether this model can be transposed onto other settings such as Africa in order to serve as a catalyst for development as well as a framework for North-South dialogue. The situation in Africa is for example not analogous to that of Eastern Europe during the time of the EU’s expansion – the weakness of many African states is much greater. Region building in Africa will therefore be as much about state building as anything else.

However, emulation of the EU model for African development and EU-Africa dialogue is not simply a matter of state capacity building. Bach argued that the EU model has been undermined by the contradictory policy orientations of the EU towards Africa. Economic liberalisation and integration in Africa has for instance been undermined by EU protectionist policies and an unwillingness to treat Africa as a single market. Democratisation in Africa meanwhile has largely been sacrificed in favour of enforcement of the status quo. Lastly, the concept of ownership is pursued along narrow security parameters. In the interest of European border control, Africa is expected to regulate its migration outflows, while European peace keeping forces steadily retreat from the continent. In sum, Bach argued that the EU’s strategic partnership with Africa is not simply a model lost in translation; it is a model which has not even ever been implemented.

The choice is not between a ‘no strings attached’ versus a Washington Consensus model of engagement between the EU and Africa. What is needed is a true strategic partnership between the EU and Africa based on a dialogue of equals, articulated in a coherent set of policies. If this does not happen, the provincialisation of Europe rather than the marginalisation of Africa is at stake.